HEAD EAST from Phoenix, Arizona, and you’ll soon find yourself in open country. The Sonoran Desert rolls to the horizon, saguaros and ocotillo standing guard over this mostly unspoiled landscape. The highway rises to Gonzales Pass, where a frontier sheriff is said to have dropped off criminals arrested in his town, after confiscating their horses and boots, and forced them to walk back to Phoenix.

The road swoops through sage-colored hills and then sets you down in the town of Superior, a former copper mining town, now a burgeoning arts community. Standing at the borderline between rolling hills and rugged mountains, Superior is the site of famed skirmishes of the Apache Wars. From the cliffs that loom above the town, Apache warriors leapt to their death rather than be taken prisoner. It’s still possible to collect the stones called Apache Tears—globular clumps of obsidian—from the ground here. You can purchase them in local gift shops, fashioned into pendants and earrings.

From Superior the highway snakes up through Devil’s Canyon, with its dramatic views and some of the best rock climbing in the country. The fenced-off mouths of mining tunnels can be seen from the highway, and some of the old workings still stand, stubborn against the forces of nature that are rusting and rotting them into the dry ground.

Some 80 miles east of Phoenix, you’ll reach the community of Globe-Miami, two towns with roots in mining and ranching, where history leaps out at every turn. Miami—still a productive mining district—preserves within its downtown a century-old streetscape, with its wide sidewalks and vintage building facades. A few miles farther up the road, Globe—Gila County seat—was once the de facto capital of territorial Arizona. Within the city limits of Globe are the well-preserved ruins of a Pueblo village that dates to around 1200 AD.

Globe and Miami are alive with history and innovation—these two towns are the site of a ground-breaking partnership with Taliesin, the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture, to apply cutting-edge architectural concepts in a rural setting—and offer abundant opportunities for outdoor recreation and arts and entertainment. But they are not our destination today. We’re headed to wilder regions.

Just after the railroad tracks in Globe, we’ll take the turnoff toward Roosevelt Lake. Our destination is found in the mountains south of its shores, eight miles deep in the Tonto National Forest: a leafy valley with a creek running through it, amid cactus-covered hills. We’re going to visit Peter Bigfoot.

South of the lake, we leave the pavement, entering forest land. The road becomes progressively rougher—first well-graded gravel, it then drops to follow the dry bed of Campaign Creek, winding among desert willow trees and catclaw bushes. A few miles in, we ascend the aptly named Car-Killer Hill, and peer down into a narrow slot canyon, through which the creek rages and storms after heavy rains.

A mile later the road descends again to follow the creek’s meandering path. At this altitude Campaign Creek runs nearly year-round (it’s the only year-round creek in Gila County). The vegetation along its banks becomes lusher, brighter green, the higher we rise in elevation. Cottonwood, sycamores, and seep willows gather by the water; wild grape vines twine among their branches. We might catch sight of white-tail deer, fox, coatimundi, or even a mountain lion.

Bumping along the unmaintained road, we finally come into view of the gate to Bigfoot’s place. A hand-painted sign reads,

Reevis Mountain School

School of Self-Reliance and Natural Healing

A Spiritual Sanctuary

Organic Farm

Retreat for Relaxation and Rejuvenation

Free Brochures and Fresh Spring Water May Be Obtained at the House

Peter Bigfoot – Founder

Another indicates, “Dogs Must Be Leashed—Chickens Roaming Free.”

Once we’re through the gate, the natural surroundings become lusher still. Inside these fences, there’s been no cattle grazing for nearly 40 years. The natural vegetation has grown in, while Bigfoot has cleared the understory to allow views among the sheltering trees. To the right, just inside the gate, we glimpse a tiny, odd-looking dwelling, looking a bit like a white mushroom with a pointed cap, with a low, Hobbit-size door under its wide eave.

The road winds among trees whose branches touch overhead. Soon we park and get out of the truck and stretch. The air is fresh, birds sing and call, a breeze rustles the leaves, the creek burbles.

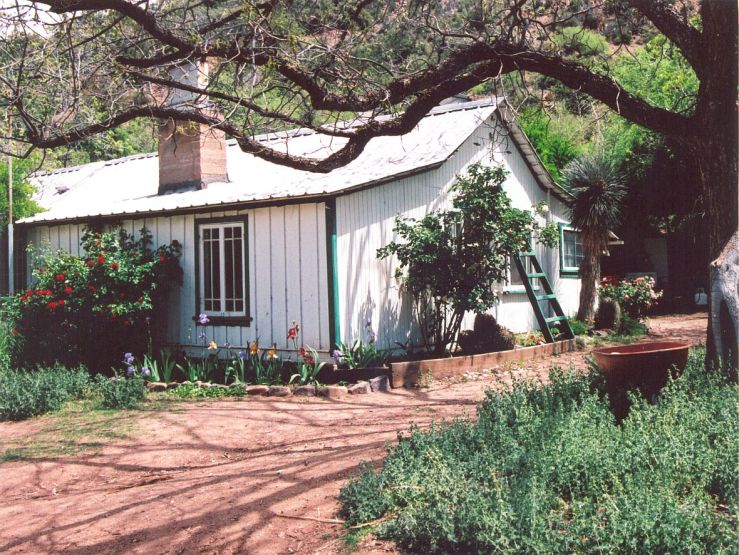

We head up to the farmhouse. It’s painted white with bright green trim, surrounded by rose bushes and irises, shaded by big old pecan trees. A couple of white geese sun themselves by the road. A rooster crows. Turkeys gobble. The place smells of soil, composted manure, and woodsmoke.

This is Reevis Mountain School of Self-Reliance, where Peter Bigfoot farms year-round and has done going on 37 years. He also teaches—wilderness survival, natural healing, and plant study—and makes a line of handcrafted herbal remedies that he sells online. Six miles from the nearest neighbor—a cattle ranch—his garden and orchard produce fruit and vegetables that enjoy high demand among a fortunate circle of Bigfoot’s longtime friends and customers.

Electricity comes from an array of solar panels; water, from Campaign Creek and two mountain springs. A changing group of work-exchangers work in the garden and tend the animals.

The man himself is most likely to be found in his vegetable garden—if he’s not in his workshop. We’re looking for a tall, lean man with a mass of white hair under a wide-brimmed hat. And there he is, wielding a hoe as if he’d been born with it in his hands.

He’ll greet you with a wave and a smile and keep on hoeing. Ask how he’s doing and he’ll invariably say, “Above ground and happy.”

At 74, Peter Bigfoot has been farming here for half his vigorous life. Respected in survival circles for his desert survival acumen and among herbalists for his wisdom in Sonoran desert plants, energetic proponent of healthful living and natural medicine, healer, teacher, mentor, and something of a prophet, Bigfoot is also a multiskilled man of the soil, like the pioneer farmers he admires: carpenter, welder, builder, leatherworker, cobbler, and more. He has the presence of six men, and although he will lament over his aging body—“This is all that’s left of me”—the man radiates health, strength, stamina, and joy.

It was on a hilltop among the low mountains south of the farm, on a warm June afternoon eight years ago, that Peter taught me to make fire. First, he consulted his watch—he keeps it on a fob, tucked into the front pocket of his blue jeans. He read out the time aloud.

Then, he sent me to bring back a branch of juniper or catclaw, while he broke the dry stalk from a yucca plant. When I returned a few minutes later with the juniper branch, he had sawed the yucca stalk into two lengths and was fashioning the longer part into a bow nearly as long as my arm, with notches at both ends; he shaved it until it had just the right amount of flex. The other piece became a drill, about half the length of the bow.

He explained that the juniper I’d found would provide the bearing piece—held atop the drill, allowing him to spin the drill under pressure—as well as the burn board, which would be positioned between the drill’s head and the ground.

When these four pieces were prepared, Peter stooped and untied his boot. He removed the lace and tied both ends to the ends of the bow, and then caught the lace with the drill and flipped it so that the lace looped around the drill. With his large stonemason’s hands he gathered a loose nest of dry, thready juniper bark and tucked it under the burn board.

Now assuming the bow-driller’s position—a crouch with one knee to the ground, the other leg held in a right angle, chest near this knee, drill held vertically between burn board and bearing piece, bow horizontal, perpendicular to the drill—he began to work the bow rapidly back and forth, with long, smooth strokes.

I looked on, impressed by his confidence and expertise. Clearly, he had done this trick many times before.

I smelled heat, and in seconds, threads of smoke began to seep from the nest of juniper bark.

Peter dropped his tools and lifted the smoking mass into his hands, blew gently to bring it to life. As flames sprouted from his palms, he bent and set the fire on the ground.

I watched the dancing flames, fascinated.

Peter consulted his watch a second time. “Twenty-six minutes,” he said.

Twenty-six minutes from the thought of fire to the living flames I beheld. If this is not impressive, I don’t know what is.

A man who makes fire: the stuff of primordial legend, of deepest myth. In some contexts, this ability might be the difference between life and death. For Bigfoot, however, it’s not really about survival. It’s about freedom—the freedom to live wild and undomesticated.

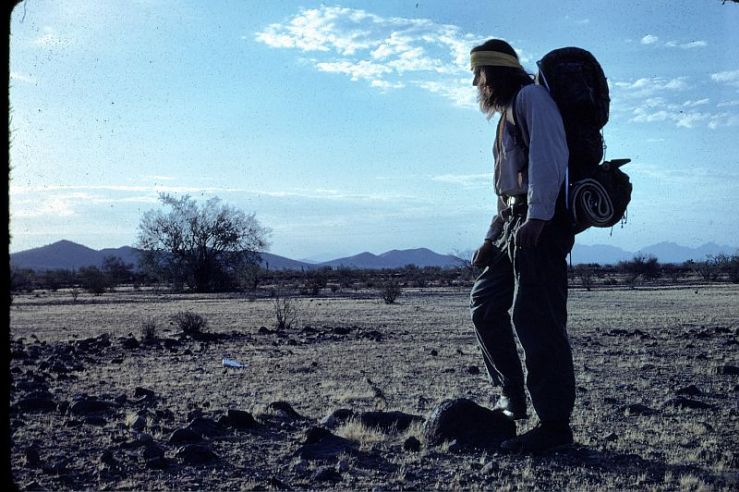

In July of 1976, during one of the hottest and driest summers on record at that time, Peter Bigfoot—then Peter Busnack—trekked 85 miles across the desert, from the place now called New River, on I-17 north of Phoenix, northeast to Four Peaks Mountain. He went alone, and he took no food or water. He navigated by maps and compass from spring to stock tank to seep to pool, and he found them dry or fouled as often as not. He foraged for his food and, when he got sick from drinking bad water, he foraged for his medicine, too. He nearly died countless times from causes ranging from dehydration to lightning.

After fifteen days on the trail, he reached his destination, the slopes of Four Peaks Mountain. Then he hitched a ride home. When his ride’s car broke down, he repaired it by the side of the road and got them all home.

Ask Bigfoot why he went out into the desert alone, to rely on this harsh environment for his needs, and quite possibly to die, and his reply will be, “I always wanted to be wild and free, like the animals in the forest.”

After that adventure, Peter became locally famous as a survival teacher, and took on the name Bigfoot. In 1979, leading a trek through the Superstition Wilderness, he came up on the land he now calls home. Through a series of happy accidents he was able to purchase it, and in 1980 he and a group of like-minded others moved there. Living in backpacking tents, they began to turn the old, ramshackle homestead into the lovely and lively spot it is today.

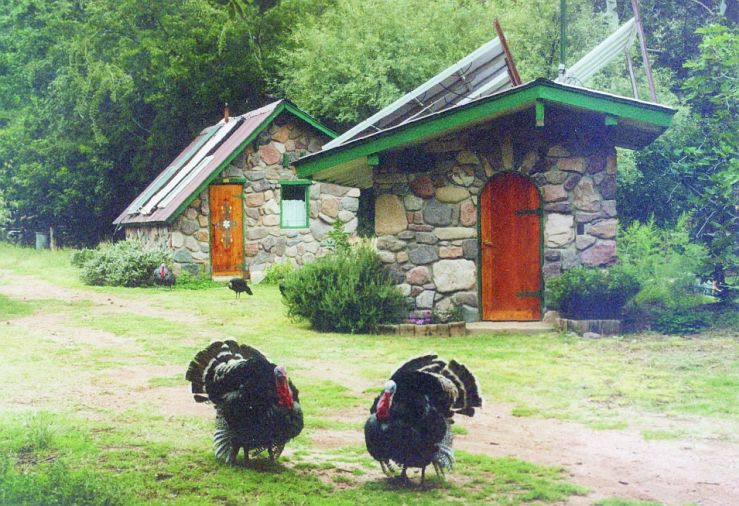

They renovated the old farmhouse, which today houses a kitchen, dining room, library, and office. They built a stone showerhouse, planted an orchard, and tilled and fenced an acre of land for a garden. Over the years, the farm added flocks of chickens and turkeys, a vineyard, a greenhouse, and a blackberry patch.

They built teepees of canvas to live in, and then gradually replaced the teepees with a modified design, a teepee-yurt combination that Bigfoot devised, called a yurpee. Bigfoot himself lives in a yurpee, heated by a woodstove in the middle. From his bathtub he can listen to Campaign Creek burble only twenty yards away.

Upwards of five hundred visitors make the trip out here every year, drawn by the stories they’ve heard of Bigfoot’s healing powers, his wilderness wisdom, or just the beauty of the place. Some travel long distances to see the farm and meet Peter Bigfoot; some are seeking help with their health—physical or spiritual. Some stumble onto the farm by accident while four-wheeling or hunting.

However, getting to Reevis Mountain School can be an adventure in itself. A heavy storm can leave the road impassable.

Bigfoot tells of the time it rained 22 inches in one month, and the road washed out so badly they couldn’t get a vehicle in or out for five months. “We packed in fifty-pound sacks of feed, and a set of solar panels,” he says.

“Those were the days when I was a rootin’ tootin’ Fig Newton.”

Originally posted at magnificentpassage.com.